Why AI adoption in organisations often gets stuck between tools and vision

4 minutes reading

It is striking how many organisations are currently in roughly the same conversation. AI is used daily, the benefits are tangible and most feel that something big is on the way – but when the discussion shifts to where we are headed, it quickly becomes either unclear or overly visionary.

Either one gets stuck in details about tools and use cases. Or one jumps straight to phrases like "AI-first", "autonomous systems" and "completely new business models", without really being able to explain what actually needs to change in between.

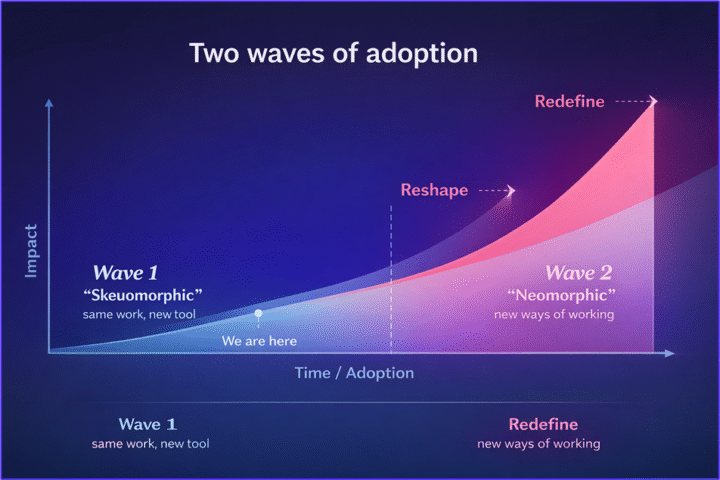

This is where the model of two waves of AI adoption is unusually useful. Not because it simplifies reality, but because it makes it possible to talk about both the current state and the direction forward at the same time – in a way that most people actually recognise.

Two waves that capture reality better than visions

Wave 1: When AI streamlines existing work

The first wave, often called skeuomorphic, is about using AI to perform the same work as today, but more efficiently. This is where most organisations currently find themselves. AI is used as support in analysis, development, documentation, communication, and decision preparation. For many, this is already obvious, and the benefits are clear.

The interesting thing is that the value in this phase rarely comes from dramatically higher quality. Instead, it comes from time savings and cognitive relief. An often underestimated value is the increased learning pace – that more ideas can be tested, evaluated, and discarded or further developed in a shorter time. This changes the pace within the organisation, even though the actual tasks remain fundamentally the same.

Wave 2: When working methods and responsibilities are redesigned around AI

The second wave, neomorphic, describes something completely different. Here, AI is used not just as support, but as part of the very design of the work itself. Working methods, roles, and sometimes entire offerings are rebuilt with AI as a prerequisite rather than an add-on. This is where the truly significant effects arise – but also where the demands on the organisation change radically.

For this reason, the model is a good way to discuss both the current situation and the direction forward. It allows us to say: what we do today is reasonable and valuable – without pretending it is the end goal.

When do you actually move from Wave 1 to Wave 2?

A crucial boundary between the two waves is not about technology, but about responsibility. As long as AI primarily supports human work – by suggesting, summarising, or accelerating – you are in Wave 1. The step into Wave 2 is taken only when AI actually owns parts of the execution or decision-making. When the human role shifts from doing the job to setting the framework, following up, and correcting.

The use of AI agents is a clear example. Not because agents themselves automatically mean Wave 2, but because they force questions about mandate, responsibility, and control. Who makes the decision? Who bears the risk? And what happens when decisions are made continuously rather than periodically?

Common misconceptions about AI adoption in organisations

A common pitfall is that organisations feel they are approaching Wave 2 when in reality they are still in Wave 1. This often happens when discussing AI-first, introducing new AI roles, or experimenting with agents – but without changing decision mandates, responsibilities, or processes.

If AI still requires human approval at every step, or is merely layered on top of existing structures, you have not actually moved beyond the first wave. This is not a failure, but it is important to be honest about where you actually stand.

This model acts as a form of reality check. It distinguishes between rhetoric and actual change.

Do you need a shared language for AI adoption?

What is actually required to succeed with AI transformation

The most crucial barrier for Wave 2 is rarely access to AI tools. It is governance.

For AI to take on greater responsibility, clear objectives, decision criteria, and frameworks within which the system can operate are required. There needs to be trust in data and metrics, as well as an organisational ability to change processes quickly when something is not working. Above all, leadership that accepts uncertainty and probability-based decisions is required, rather than full control at every single step.

Without this, AI will always need to "ask for permission." And thus, it remains an advanced support tool, no matter how sophisticated the technology is.

How AI is changing roles, responsibilities and decision-making

The roles that are changing first in Wave 2 are often those that work closely with prioritisation, synthesis and coordination. Product owners, analysts, project managers and senior specialists have tasks that largely involve weighing options and making decisions – exactly the area where AI is gaining significant leverage rapidly.

At the same time, there are processes that strongly resist neomorphic redesign. Budgeting, compliance and personnel evaluation are typical examples. Not because AI lacks capacity, but because accountability, legality and governance are deeply embedded in the structure. The resistance is almost always in governance, not in the technology.

This is also linked to how risk is distributed. In Wave 1, the risk is primarily in execution – was the analysis correct, was the code accurate? In Wave 2, the risk shifts to how decision frameworks and systems are designed. The risk moves from the individual level to the system and organisational level.

Learning, delivery and irreversible changes

Wave 2 requires room for experimentation, but also discipline. Organisations that succeed separate stable, business-critical flows from more experimental AI initiatives. They allow learning, but with clear criteria for when experiments should be scaled up or ended.

It is also important to understand that some changes in Wave 2 are difficult to roll back. When AI is allowed to make decisions in real time, when customer experiences are built with AI as a prerequisite, or when roles are redefined from execution to supervision – then behaviours and expectations change. Once they are established, reverting becomes both costly and painful.

A concrete example: Apotea

A company that clearly illustrates the direction towards Wave 2 is Apotea. Their ambition is not for AI to support processes and people, but for processes and people to support AI. It is a seemingly small wording, but it signals a fundamental shift in how work, responsibility, and value creation are understood.

AI adoption in organisations requires a new conversation, not more tools

What makes this a good way to talk about both the current situation and the direction forward is that the model neither diminishes the work that is already being done nor romanticises the future. It creates a common language to discuss what is actually changing – and what is not yet doing so.

For many organisations, the most important conversations begin when you dare to ask three simple questions:

- Where are we today, and why?

- What responsibility does AI actually hold with us?

- What would need to change for the next wave to be realistic?

Answers are rarely simple. But that is precisely where the development begins.

Related news

When transport planning becomes a bottleneck in production

Successfully completed global go-live at IPCO, – 33 sites, 31 countries